Across healthcare there has been a move toward greater accountability. Funding bodies are no longer interested in funding activity, and are demanding outcomes. The recent review of mental health services by the National Mental Health Commission was explicit in saying as much.

This trend is only in its infancy in the mental health space, but as conservative governments push forward the twin agenda of contestability and case-mix funding, NGOs are already feeling the pressure to justify what they do with the money they are granted.

To my mind, the limited of implementation of routine evaluation by private practicing psychologists represents the single greatest strategic threat to the on-going maintenance of the Better Access program. Governments are increasingly refusing to pay for services where the outcomes are unclear, and this program sits as a large ticket expense item with very limited evidence of effectiveness.

Routine Practice – What it’s not

I do a lot of training workshops nationally and internationally around outcome based practice, and I often hear psychologists explain to me that they believe they are already undertaking routine evaluation, when the reality could not be further from the truth.

“I give Pre and Post DASS-21s to check my outcomes.”

No you don’t. You give “Pre” DASS-21s, and every once in a while you collect the odd post data point. The reality is that the modal number of sessions for psychotherapy is one, closely followed by two. Even when clients don’t drop out prematurely, the reality is that in modern private practice, clients rarely mutually decide with the therapist when their final session will be. They are far more likely to book an eighth session with you, and some time after their seventh session, they decide they don’t need to come back. The small handful of clients for whom you do have both pre and post data is such an unrepresentative sample that it usually grossly overestimates your effectiveness. No funding body takes these comparisons seriously (nor should they).

“I don’t need to use routine evaluation, because I only use evidence-based practices and we already know how effective they are.”

No we don’t. In meta-analyses of psychotherapy effect sizes, we have come to expect an effect size of d = 0.7. However, in real world outcome studies, the effect size looks more like d = 0.2. Unless you have evidence to the contrary, I am going to assume that the real world data applies to you and your practice, and so will everyone else.

“I am highly trained and am very sensitive to ruptures in the therapeutic alliance.”

Research tells us that therapists are the least accurate judges of therapeutic alliance, and that alliance as rated by therapists is not a particularly strong contributor to outcomes. When you hear the phrase “the best predictor of outcome is therapeutic alliance”, make sure you add on the clause “… as rated by the client”. Therapists are generally not effective raters of the strength of alliance not because we are insensitive, but because the clients’ experience is naturally subjective. Without asking them, we have no way of knowing.

So now we know what routine evaluation isn’t; let’s look at what it is.

There are three major elements of routine evaluation that have been empirically demonstrated to be helpful:

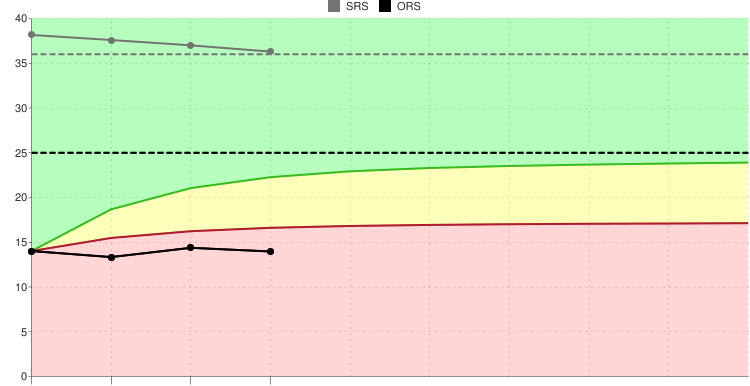

- session by session tracking of psychometric outcomes;

- seeking client feedback of each session and attending to ruptures in therapeutic alliance; and

- entering outcomes into a database which has built in decision support algorithms.

Session by session tracking.

There are a number of tools available that allow clinicians to track outcomes. There is no magic in which tool you use, and different instruments may be a better fit for different clinical What makes a good instrument is as follows environments.

- brief enough to be used every session;

- psychometrically robust; and

- relevant to your population.

Currently, the two leading tools in this space are the Outcome Rating Scale (by Miller and colleagues) and the OQ45 by Michael Lambert. I have used both and have experienced pros and cons in each. I am also collaborating on a progress-monitoring version of the DASS with Professor Kim Halford, hopefully to be published late next year.

The starting point for any clinician looking to track outcomes is to choose a measure. There is an excellent review article of some of the leading measures available for this purpose available here.

Client feedback

This is another area that psychologists often feel that they do well in, however the data indicates otherwise.

Simply asking a client how they found their session with you will lead to a falsely optimistic view of things. Like all of us, clients are bound by social conventions and they often find it hard to give offense (obviously, not all clients feel this way). When asked if they found therapy helpful, clients will often answer enthusiastically and positively.

Simply asking a client how they found their session with you will lead to a falsely optimistic view of things. Like all of us, clients are bound by social conventions and they often find it hard to give offense (obviously, not all clients feel this way). When asked if they found therapy helpful, clients will often answer enthusiastically and positively.

The trick is for the therapist to ask the question in such a way that the client feels genuinely empowered to give negative feedback. There are a few tricks to this, for example:

- ask for feedback with sufficient time (if you ask as you are pushing someone out the door, it is pretty clear you don’t care about the answer);

- make it clear why the feedback is important (what the client has to say will contribute to guiding their treatment);

- choose words that indicate you care about their answer rather than suggesting polite small talk; and

- stress that the feedback is for you to improve, rather than part of some organisational quality assurance program.

A good rule of thumb is if you are receiving 100% positive feedback, it doesn’t indicate that you are doing 100% good work, rather it signifies that you 100% do not know how to ask for feedback properly.

Automation

Even the most enthusiastic therapist will eventually lose interest in pencil and paper measures and whilst Scott Miller’s ORS and SRS are free for individuals in pencil and paper form, you can be pretty sure that you or your team won’t use them for long enough to get much benefit.

Make it easy on yourself, spend a few dollars and buy an APP. Some examples are:

- MyOutcomes;

- FITOutcomes;

- Pragmatic Tracker; and

- TOMS

The above are excellent products and include the Miller tools, and are cheaply available on app stores.

OQ Analyst offers the Lambert suite of measures (OQ45, Working Alliance inventory and the briefer OQ). Whilst the product is a bit clunkier, the psychometrics of these tools are slightly better than the Miller suite of measures. There are also other packages available with the tools listed in the earlier link.

(N.B.; Aaron is a certified trainer with Scott Miller’s group at The International Centre for Clinical Excellence, but does not receive any financial incentive for recommending these products. In fact, he remains firmly agnostic regarding which product is better, and personally uses a different suite altogether.)

Culture

The final piece of the puzzle is culture. There is a long history of failed outcome implementations in mental health, as any of you who lived through the public sector roll out of HoNOS, HoNOSca, LSP etc., will attest. There is a reason that these approaches fail.

The culture of an organisation needs to change. Clinicians will be highly resistant to outcome measures when they feel they are being used for performance management, and even more resistant if they feel they are being collected as part of pointless bureaucratic micro-management. Convincing clinicians that the primary aim of outcome collection is improved patient care is essential.

Truly behaving as an evidence based therapist is deceptively simple. Each of the above processes are actually relatively simple to implement. However, there are very few practices who can truly say that they have implemented this fully within Australia. The inspiration for practices and organisations to move toward this outcome informed approach often comes from coalface clinicians who have realised the benefits this approach brings to their clients. However, in order to foster organisational sustainability, buy in and sponsorship from management is required. It takes careful planning by management to make this transition in impetus without losing the good will of clinicians.

If you are considering implementing a feedback informed approach at your practice, read widely, consult with colleagues who have gone down this path themselves and consider that this process will take at least a 12 months. It is a process of change management, rather than a simple case of buying some tools and paying for once-off training.

Dr Aaron Frost is a Clinical Psychologist in private practice with a long interest in mental health service delivery. He has established a group private practice entirely around the collection of outcome data, both to improve client outcomes, but also to improve accountability. He consults to a range of small and large agencies interested in customising this approach to their setting.